Modeling Boolean Logic (Syntax, Semantics, and Sets)

In this chapter, we'll start writing a new model from scratch to meet 3 broad goals:

- expanding Forge's expressive power to support sets and relations;

- modeling more recursive concepts in a language without recursion; and

- modeling a syntax for a language, along with its semantics.

You can find the completed models here.

Modeling Boolean Formulas

If you've spent time writing programs, then you've already spent a lot of time working with boolean formulas. E.g., if you're building a binary search tree in Java, you might write something like this to check the left-descent case:

if(this.getLeftChild() != null &&

this.getLeftChild().value < goal) {

...

}

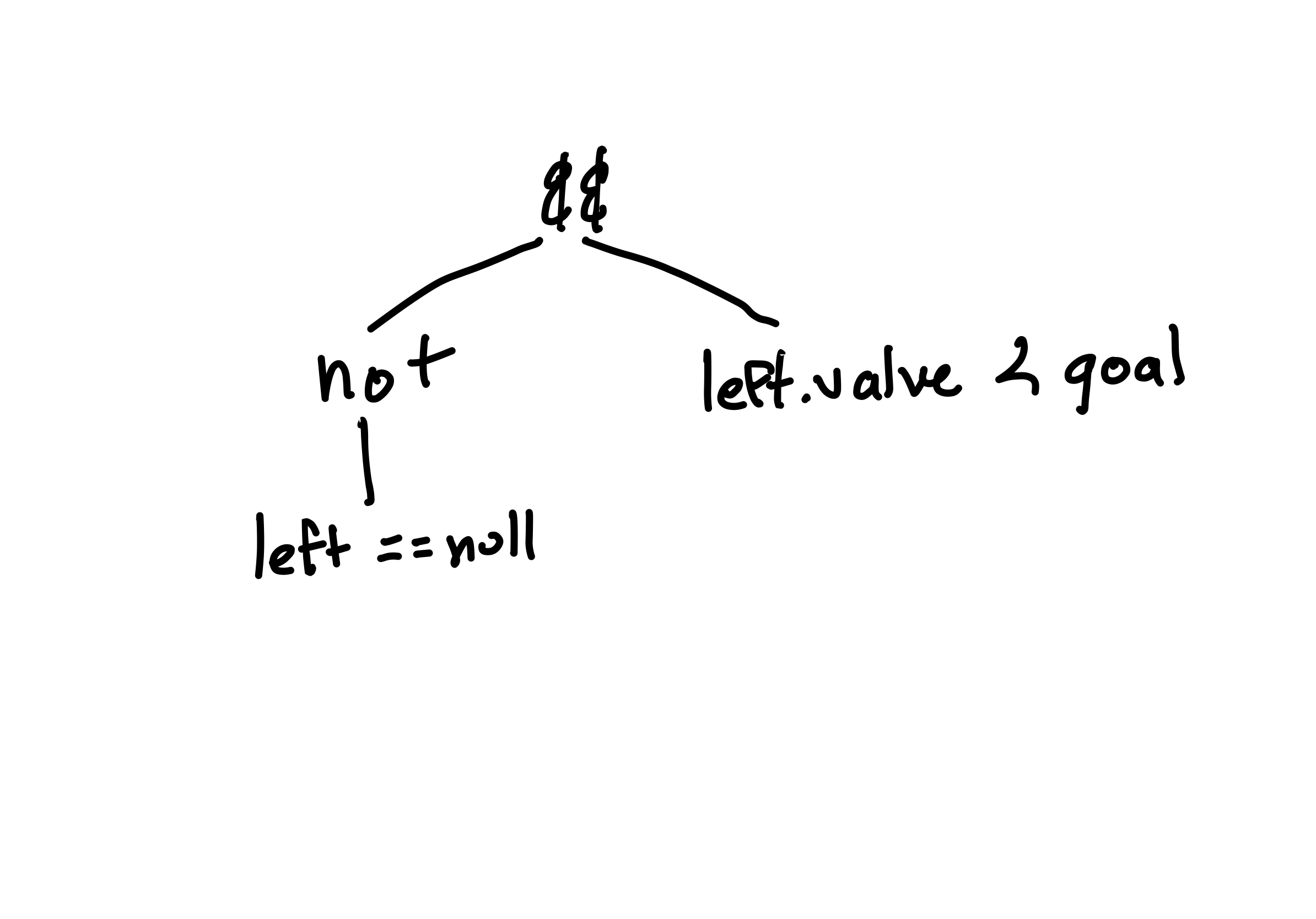

The conditional inside the if is a boolean formula with two boolean variables (also sometimes called atomic propositions) corresponding to leftChild == null and leftChild.value < goal. A ! (not) negates the equality check, and a single && (and) combines the conditions. The syntax of the conditional forms a tree, with atoms for the two boolean variables, the not and the and:

Modeling Boolean Formulas

Let's define some types for formulas. Like we've done before when defining a hierarchy of types, we'll make an abstract sig to represent the collection of all kinds of formulas, and have child sigs that represent specific kinds:

-- Syntax: formulas

abstract sig Formula {}

sig Var extends Formula {}

sig Not extends Formula {child: one Formula}

sig Or extends Formula {o_left, o_right: one Formula}

sig And extends Formula {a_left, a_right: one Formula}

-- If we really wanted to, we could add `Implies`, `IFF`, etc. in the same way.

Forge doesn't allow re-use of field names between sigs. If you try, you'll get an error that says the name is already used. So we need to name the left and right children of the And and Or types differently. Hence the o_ and a_ prefixes.

Wellformedness

As always, we need a notion of wellformedness. What would make a formula tree "garbage"? Well, if the syntax tree contained a cycle, the tree wouldn't be a tree, and the formula wouldn't be a formula! We'll write a wellformed predicate where an assertion like this will pass:

pred trivialLeftCycle {

some a: And | a.a_left = a

}

pred notWellformed { not wellformed }

assert trivialLeftCycle is sufficient for notWellformed

(TODO: I don't like the need to create a secondary helper notWellformed. Discuss with SP.)

Like in binary trees, there are multiple fields that a cycle could use. Then, we only needed to worry about left and right; here there are many more. Let's build a helper predicate that evaluates whether a formula is a smaller part of another:

-- IMPORTANT: remember to update this if adding new formula types!

pred subFormulaOf[sub: Formula, f: Formula] {

reachable[sub, f, child, a_left, o_left, a_right, o_right]

}

At first, this might seem like a strange use of a helper. There's just one line, and all it does is call the reachable built-in predicate. However, we probably need to check for subformulas in multiple places in our model. And, we might anticipate a need to add more formula types (maybe we get around to adding Implies). Then we need to remember to add the fields of the new sig everywhere that reachable is used. And if we leave one out, we probably won't get an error. So making this helper is just good engineering practice; this way, we minimize the number of places that need the change.

pred wellformed {

-- no cycles

all f: Formula | not subFormulaOf[f, f]

}

Recall that we use wellformed to exclude "garbage" instances only, analogously to filtering an input generator in property-based testing. The stuff we might want to verify (or build a system to enforce) goes elsewhere—or else Forge will exclude any potental counterexamples.

We'll want to add wellformed to the first example we wrote, but it should still pass. Let's run the model and look at some formulas! We could just run {wellformed}, but that might be prone to giving uninteresting examples. Let's try identifying the root node in our run constraint, which would let us ask for something more complex:

run {

wellformed

some top: Formula | {

all other: Formula | top != other => {

subFormulaOf[other, top]

}

}

} for exactly 8 Formula

Try running this. You should see some example formula trees; we've modeled the syntax of boolean logic.

Exercise: Write at least one more positive and one more negative test for wellformed in this model.

Exercise: Why didn't we add a constraint to prevent nodes from having multiple parents? That is, why didn't we prevent an instance like this? (And, in light of that, is it really fair to call these "trees"?)

TODO: add image

Think, then click!

If we wanted to exlude "sharing" of child formulas, we'd need to allow multiple nodes to have the same meaning. E.g., if we had a variable x, we'd need to allow multiple Var atoms to represent x, which would greatly complicated the model and increase the size of its instances. Instead, we let one Var atom be re-used in multiple contexts.

So, while the instances aren't (strictly speaking) trees, they represent trees in an efficient way.

The Meaning Of Boolean Circuits

What's the meaning of a formula? So far they're just bits of syntax in isolation; we haven't defined a way to understand them or interpret them. This distinction between syntax and its meaning is really important, and touches every aspect of computer science. Indeed, it deeply affects anywhere we use a language.

To see why, let's go back to that Java BST example, with the boolean conditional:

if(this.getLeftChild() != null && this.getLeftChild().value < goal) {

...

}

Exercise: Suppose that the getLeftChild() method increments a counter whenever it is called. Suppose the counter is 0 before this if statement runs. What will it be afterward?

Think, then click!

It depends!

- If the left-child is non-null, the counter will hold

2afterward, becausegetLeftChild()will be called twice. - If the left-child is null, and we're working in a language like Java, which "short circuits" conditionals, the counter would be

1since the second branch of the&&wouldn't execute.

In another language, one that didn't have short-circuiting conditionals, the counter might be 2 in both cases. And in yet another language, where getLeftChild() might be cached and only called once, both counters might be 1!

What's the point?

If we don't know the meaning of that if statement and the and within it, we don't actually know what will happen! Syntax can mislead us, especially if we have pre-existing intuitions. And if we want to reason about what a piece of syntax does, we need to understand what the syntax means.

Right now we're modeling boolean formulas. So let's understand the meaning of formulas; sometimes this is called their semantics.

Exercise: What can I do with a formula? What kind of operations is it meant to enable?

Think, then click!

If I have a formula, I can plug in various values into its variables and read off the result: does the overall formula evaluate to true or false when given those values? This is what we want to encode in our model.

Let's think of a boolean formula like a function from sets of variable values to a result boolean.

We'll need a way to represent "sets of variable values". Sometimes these are called a "valuation", so let's make a new sig for that.

sig Valuation {

-- [HELP: what do we put here? Read on...]

}

We have to decide what fields a Valuation should have. Once we do that, we might start out by writing a recursive predicate or function, kind of like this pseudocode:

pred semantics[f: Formula, val: Valuation] {

f instanceof Var => val sets the f var true

f instanceof And => semantics[f.a_left, val] and semantics[f.a_right, val]

...

}

This won't work! Forge is not a recursive language; you won't be able to write a predicate that calls itself like this. So we've got to do something different. Let's move the recursion into the model itself, by adding a mock-boolean sig:

one sig Yes {}

and then adding a new field to our Formula sig (which we will, shortly, constrain to encode the semantics of formulas):

satisfiedBy: pfunc Valuation -> Yes

This works but it's a bit verbose and quite tangled. It'd be more clear to just say that every formula has a set of valuations that satisfy it. But so far we haven't been able to do that.

Language change!

First, let's change our language to #lang forge. This gives us a language with more expressive power, but also some subtleties we'll need to address.

This language is called Relational Forge, for reasons that will become apparent. For now, when you see #lang forge rather than #lang froglet, expect us to say "relational", and understand there's more expressivity there than Froglet gives you.

Now, we can write that every formula is satisfied by some set of valuations:

abstract sig Formula {

-- Work around the lack of recursion by reifying satisfiability into a field.

-- f.satisfiedBy contains an instance IFF that instance makes f true.

-- [NEW] Relational Forge lets us create fields that contain _sets_ of values.

satisfiedBy: set Valuation

}

We can now infer what field(s) Valuation should have. A Valuation isn't a formula, so it won't have a satisfiedBy field, but it does need to contain something.

Exercise: What does a Valuation contain, and how does that translate to its field(s) in Forge?

Think, then click!

sig Valuation {

trueVars: set Var

}

Now we can encode the meaning of each formula as a predicate like this:

-- IMPORTANT: remember to update this if adding new fmla types!

-- Beware using this fake-recursion trick in general cases (e.g., graphs with cycles)

-- It's safe to use here because the data are tree shaped.

pred semantics

{

-- [NEW] set difference

all f: Not | f.satisfiedBy = Valuation - f.child.satisfiedBy

-- [NEW] set comprehension, membership

all f: Var | f.satisfiedBy = {i: Valuation | f in i.trueVars}

-- ...

}

Exercise: We still need to say what f.satisfiedBy is for Or and And formulas. What should it be? (You might not yet know how to express it in Forge, but what should satisfy them, conceptually? Hint: think in terms of what satisfies their left and right subformulas.)

Think, then click!

We'd like Or to be satisfied when either of its children is satisfied. In contrast, And requires both of its children to be satisfied. We'll use union (+) and intersection (&) for this.

pred semantics

{

-- [NEW] set difference

all f: Not | f.satisfiedBy = Valuation - f.child.satisfiedBy

-- [NEW] set comprehension, membership

all f: Var | f.satisfiedBy = {i: Valuation | f in i.trueVars}

-- [NEW] set union

all f: Or | f.satisfiedBy = f.o_left.satisfiedBy + f.o_right.satisfiedBy

-- [NEW] set intersection

all f: And | f.satisfiedBy = f.a_left.satisfiedBy & f.a_right.satisfiedBy

}

In hindsight: yes, this is why you can't use + for integer addition in Froglet; we reserve the + operator to mean set union.

Is That All?

No. In fact, there are some Forge semantics questions you might have. That's not a joke: are you sure that you know the meaning of = in Forge now? Suppose I started explaining Forge's set-operator semantics like so:

- Set union (

+) in Forge produces a set that contains exactly those elements that are in one or both of the two arguments. - Set intersection (

&) in Forge produces a set that contains exactly those elements that are in both of the two arguments. - Set difference (

-) in Forge produces a set that contains exactly those elements of the first argument that are not present in the second argument. - Set comprehension (

{...}) produces a set containing exactly those elements from the domain that match the condition in the comprehension.

That may sound OK at a high level, but you shouldn't let me get away with just saying that.

Exercise: Why not?

Think, then click!

What does "produces a set" mean? And what happens if I use + (or other set operators) to combine a set and another kind of value? Am I even allowed to do that? If so, what values can I combine with sets?

This isn't a new question! It comes up in programming contexts, too.

- What happens when you add together a

floatand anintin Python? The result is automatically converted to afloat. - What happens if you do the same in (say) OCaml? You'll get a type error unless you explicitly say to convert the

intto afloat.

So, by analogy, which of these options does Forge use?

In conversation, we're often dismissive of semantics. You'll hear people say, in an argument, "That's just semantics!" (to mean that the other person is being unnecessarily pedantic and quibbling about technicalities, rather than engaging). But when we're talking about how languages work, precise definitions matter a lot!

In Relational Forge, all values are sets. A singleton value is just a set with one element, and none is the empty set. So = is always set equality in Relational Forge. From now on, we'll embrace that everything in Relational Forge is a set, but introduce the ideas that grow from that fact gradually, resolving potential confusions as we go.

The fact that all values in Relational Forge are sets means that +, &, etc. and even = are always well-defined. However, our natural intuitions about how sets are different from objects can cause problems with learning Forge like this to start, and the learner's background is a major factor. Not everyone has had a discrete math class (or remembers their discrete math class). So, we start in a language where the power of sets is drastically reduced so that we can focus early on essential concepts like constraints and quantification.

On the other hand, sets are incredibly useful. Hence this chapter.

Returning to well-formedness

Now we have a new kind of ill-formed formula: one where the semantics haven't been properly applied. So we enhance our wellformed predicate:

pred wellformed {

-- no cycles

all f: Formula | not subFormulaOf[f, f]

-- the semantics of the logic apply

semantics

}

Some Validation

Here are some examples of things you might check in the model. Notice that some are:

- validation of the model (e.g., that it's possible to have instances that disagree on which formulas they satisfy); and others are

- results about boolean logic that we might prove in a math course, like De Morgan's Laws.

Consistency Checks

-- First, some tests for CONSISTENCY. We'll use test-expect/is-sat for these.

test expect {

nuancePossible: {

wellformed

-- [NEW] set difference in quantifier domain

-- Exercise: why do we need the "- Var"?

some f: Formula - Var | {

some i: Valuation | i not in f.satisfiedBy

some i: Valuation | i in f.satisfiedBy

}

} for 5 Formula, 2 Valuation is sat

---------------------------------

doubleNegationPossible: {

wellformed

some f: Not | {

-- [NEW] set membership (but is it "subset of" or "member of"?)

f.child in Not

}

} for 3 Formula, 1 Valuation is sat

}

Properties of Boolean Logic

-- What are some properties we'd like to check?

-- We already know a double-negation is possible, so let's write a predicate for it

-- and use it in an assertion. Since it's satisfiable (above) we need not worry

-- about vacuous truth for this assertion.

pred isDoubleNegationWF[f: Formula] {

f in Not -- this is a Not

f.child in Not -- that is a double negation

wellformed

}

pred equivalent[f1, f2: Formula] {

-- Note that this predicate is always with respect to scopes/bounds. That is, "equivalent"

-- here isn't real logical equivalence, but rather whether there is a Valuation in a given

-- instance on which the two formulas disagree.

f1.satisfiedBy = f2.satisfiedBy

}

assert all n: Not | isDoubleNegationWF[n] is sufficient for equivalent[n, n.child.child]

for 5 Formula, 4 Valuation is unsat

-- de Morgan's law says that

-- !(x and y) is equivalent to (!x or !y) and vice versa. Let's check it.

-- First, we'll set up a general scenario with constraints.

pred negatedAnd_orOfNotsWF[f1, f2: Formula] {

wellformed

-- f1 is !(x and y)

f1 in Not

f1.child in And

-- f2 is (!x or !y)

f2 in Or

f2.o_left in Not

f2.o_right in Not

f2.o_left.child = f1.child.a_left

f2.o_right.child = f1.child.a_right

}

assert all f1, f2: Formula |

negatedAnd_orOfNotsWF[f1, f2] is sufficient for equivalent[f1, f2]

for 8 Formula, 4 Valuation is unsat

-- If we're going to trust that assertion passing, we need to confirm

-- that the left-hand-side is satisfiable!

test expect {

negatedAnd_orOfNotsWF_sat: {

some f1, f2: Formula | negatedAnd_orOfNotsWF[f1, f2]

} for 8 Formula, 4 Valuation is sat

}

Looking Forward

It turns out that sets are remarkably useful for describing relationships between objects in the world. We'll explore that further in the next sections.